On Saturday 8th September 2018 I gave a talk to researchED London about the pupil premium. It was too long for my 40-minute slot, and the written version is similarly far too long for one post. So I am posting my argument in three parts [pt II is here and pt III is here].

Every education researcher I have met shares a desire to work out how we can support students from disadvantaged backgrounds as they navigate the education system. I wrote my PhD thesis about why school admissions help middle class families get ahead. No politician is crazy enough to do anything about that; but they have been brave enough to put their money where their mouth is, using cash to try to close the attainment gap. This series of blog posts explains why I think the pupil premium hasn’t worked and why it diverts the education system away from things that might work somewhat better. I suggest it is time to re-focus our energies on constructing classrooms that give the greatest chance of success to those most likely to fall behind.

Money, money, money…

We think about attaching money to free school meal students as a Coalition policy, but the decision to substantially increase the amount going to schools serving disadvantaged communities came during the earlier Labour Government. The charts below come from an IFS paper that shows how increases in funding were tilted towards more disadvantaged schools from 1999 onwards. The subsequent ‘pupil premium’ (currently £1,320 for primary and £935 for secondary pupils) really was just the icing on the cake.

However, the icing on the cake turned out to have a slightly bitter taste, for it came with pretty onerous expenditure and reporting requirements:

- The money must be spent on pupil premium students, and not simply placed into the general expenditure bucket

- Schools must develop and publish a strategy for spending the money

- Governors and Ofsted must check that the strategy is sound and that the school tracks the progress of the pupil premium students to show they are closing the attainment gap

The pupil premium does not target our lowest income students

Using school free school meal eligibility as an element in a school funding formula is a perfectly fine idea, but translating this into a hypothecated grant attached to an actual child makes no sense. The first reason why is that free school meals eligibility does not identify the poorest children in our schools. This was well known by researchers at the time the pupil premium was introduced thanks to a paper by Hobbs and Vignoles that showed a large proportion of free school meal eligible children (between 50% and 75%) were not in the lowest income households (see chart below from their paper). One reason why is that the very act of receiving the means-tested benefits and tax credits that in turn entitle the child to free school meals raises their household income above the ‘working poor’.

Poverty is a poor proxy for educational and social disadvantage

Even if free school meal eligibility perfectly captured our poorest children, it would still make little sense to direct resources to these children since poverty is a poor proxy for the thing that teachers and schools care about: the educational and social disadvantage of families. Children who come from households who are time-poor and haven’t themselves experienced success at school often do need far more support to succeed at school, not least because:

- Their household financial and time investment in their child’s education is frequently lower

- Their child’s engagement in school and motivation could be lower

- The child’s cognitive function might lead them to struggle (of which more in part 3)

These are social, rather than income, characteristics of the family.

Pupil premium students do not have homogeneous needs

There are pupil premium students who experience difficulties with attendance and behaviour; there are pupil premium students who do not. There are non-pupil premium students who experience difficulties with attendance and behaviour; there are those who do not. Categorising students as a means of allocating resources in schools is very sensible, if done along educationally meaningful lines (e.g. the group who do not read at home with their parents; the group who cannot write fluently; the group who are frequently late to school). Categorising students as pupil premium or not is a bizarre way to make decisions about who gets access to scarce resources in schools.

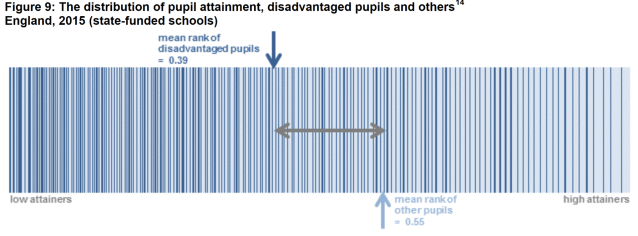

Yes, there are mean average differences by pupil premium status in attendance, behaviour and attainment. However, the group means mask the extent to which pupil premium students are almost as different from each other than they are from the non-pupil premium group of students. The DfE chart below highlights this nicely.

In his book, Factfulness, the great, late Hans Rosling implores us not to overuse this type of analysis of group mean averages to make inferences about the world. He explains that ‘gap stories’ are almost always a gross over-simplification. They encourage us to stereotype groups of people who are not as dissimilar to others as the mean average would have us believe.

Why do we like these ‘gap stories’? We like them because we humans like the pattern forming that group analysis facilitates, and having formed the gap story, we are then naturally drawn to thinking of pupil cases that conform to the stereotypes.

Your school’s gap depends on your non-PP demographic

I’ve explained how the pupil premium group in schools do not have a homogeneous background and set of needs. Students not eligible for the pupil premium are even more diverse.

When we ask schools to monitor and report their pupil premium attainment gap, the size of the gap is largely a function of the demographic make-up of the non-pupil premium students at the school. Non-pupil premium students include the children of bus drivers and bankers; it is harder to ‘close the gap’ if yours are the latter. Many schools that boast a ‘zero’ gap (as did one where I was once a governor) simply recruit all their pupils from one housing estate where all the residents are equally financial stretched and socially struggling, though some are not free school meal eligible. Schools that serve truly diverse communities are always going to struggle on this kind of accountability metric.

Tracking whether or not ‘the gap’ has closed over time is largely meaningless, even at the national level

There are dozens of published attainment gap charts out there, all vaguely showing the same thing: the national attainment gap isn’t closing, or it isn’t closing that much. None of them are worth dwelling on too much since the difference between average FSM and non-FSM attainment is very sensitive to two things that are entirely unrelated to what students know:

- We regularly change the tests and other assessments that we bundle into attainment measures at age 5, 7, 11 and 16. This includes everything from excluding qualifications, changing coursework or teacher assessment mix, to rescaling the mapping of GCSE grades to numerical values. Generally speaking, changes that disproportionately benefit higher attaining students widen the gap.

- The group of students labelled as pupil premium at any point in time is affected by the economic cycle, by changes in benefit entitlements and by changes to the list of benefits that attract free school meals. For example, recessions tend to close the gap because they temporarily bring children onto free school meals who have parents more attached to the labour market.

It is also worth noting that FSM eligibility falls continuously from age 4 onwards as parents gradually choose (or are forced) to return to the labour market. This means comparisons of FSP, KS1, KS2 and KS4 gaps aren’t interesting.

Don’t mind your own school gap

Your school’s attainment gap, whether compared with other schools, compared with your own school over time, or compared across Key Stages, cannot tell you the things you might think it can, for all the reasons listed above.

Moreover, it isn’t possible for a school to conduct the impact analysis required by DfE and Ofsted to ‘prove’ that their pupil premium strategy is working for all the usual reasons. Sample sizes in schools are usually far too small to make any meaningful inferences about the impact of expenditure, and no school ever gets to see the counterfactual (what would have happened without the money).

What’s coming up…

Part II explains how reporting requirements drive short-term, interventionist behaviour

Part III asks whether within-classroom inequalities can ever be closed

(Punchline for the nervous… No, I don’t think the pupil premium should be removed. I suggest it should be rolled into general school funding.)

Pingback: The pupil premium is not working (part II): Reporting requirements drive short-term, interventionist behaviour – Becky Allen's musings on education policy

Pingback: The pupil premium is not working (part III): Can within-classroom inequalities can ever be closed? – Becky Allen's musings on education policy

Pingback: Useful bits and pieces for evidence informed teaching – A Chemical Orthodoxy

Pingback: Becky Allen: Pupil Premium Blog – SCHOOLS NorthEast Blog

Pingback: To address underachieving groups, teach everyone better. | teacherhead

Reblogged this on Special and Additional and commented:

getting back into reading about educational policy and its effect on learners.

Pingback: TSAOWI presents: Pupil Premium (PP) – The Subtle Art Of Winging It

Pingback: Pupil Premium – does it work? | Faith in Learning

Pingback: Making Pupil Premium work the aftermath of @profbeckyallen ‘s #rED18 speech | Leading Together

Pingback: Proof – the final frontier for teachers – Peer Reviewed Education Blog

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Dear Becky

Recently, at one of our local headteachers meetings, one of our colleagues was raving about your theories about the pupil premium.

I know that this may not be possible but we were just wondering whether you might be able to speak at one of our forthcoming St Albans Headteacher conferences? We have one on 25th January and another on 5th July.

We would be looking for about a 2 to 3 hour talk during the morning.

Please let me know if you would be willing to do it.

Many thanks indeed

Andrew Farrugia

Headteacher

Garden Fields JMI

Pingback: The pitfalls of the pupil premium – a view through different eyes

Pingback: @teacherhead Update #1. October ’18. | teacherhead

Pingback: More evidence-based argument on the ‘attainment gap’ fallacy | Roger Titcombe's Learning Matters

Pingback: IFS study finds “remarkable” refocusing of education spending towards poorer pupils – Schools North East Blog

Pingback: Pupil Premium accountability | Roger Titcombe's Learning Matters

Pingback: Born in the USA | ianfrostblog

Pingback: Dolphins and Butterflies | ianfrostblog

Pingback: The fall and rise of educational orthodoxy – 2018 revisited – EduContrarian

Pingback: COPIED WORK/NOT MINE.JUST TOUCHED BY IT – NAMUKAMBA EDUCATION CENTRE

Pingback: Teaching – Effective Interventions – Malcolm Drakes's Blog

Pingback: New figures show impact of disadvantage and ethnicity on Progress 8 – Schools North East Blog

Pingback: Tackling disadvantage: Selected research | impact.chartered.college

Pingback: Back to the future… A time machine of how poverty has been addressed within education, through the ages… – Big Imaginations

Pingback: Careering towards a curriculum crash? – Becky Allen

Pingback: What difference has the Pupil Premium made to school intakes and outcomes in England? – Edlines: The Ednorth Blog

Hello Becky. I have lost your piece on Curriculum is it possible to send to me?

Also wondering why you could not show my previous comment on PP.

Thanks for your stuff. Really useful for me as a governor with PP responsibility.

Pingback: Literacy – Providing the Equipment to Climb the Curriculum Mountain – TACKLING INEQUALITY IN ENGLISH EDUCATION

Pingback: What Teachers Tapped This Week #50 - 10th September - Teacher Tapp

Pingback: Once Again, the Government is Using Disadvantaged Children to Pursue Harmful Policies – LeftInsider

Pingback: Mind The Gap: Education at a premium and the missing year of the 2020 : PART 1 – Traditionally Speaking