I have been thinking about social inequalities and education for the past decade and feel like I’m walking a well-trodden path that has a hopeful ending. Perhaps by telling you where it leads it’ll help you get to a productive destination quicker.

I’ve spent my whole research career thinking that our best hope for fixing educational inequalities is to shuffle children, teachers and money across schools and/or classrooms. That is why I have spent so much time writing about school admissions and choice, measuring school performance, school funding and the pupil premium, and the allocation of teachers to schools and to classes within schools.

We have made essentially zero progress in England in closing the attainment gap between children who live in poorer and richer households. Zero. It is easy to feel despondent about this and wonder whether no solutions lie within the education system.

But two things that have happened over the summer – my daughter learning to swim and listening to Kris Boulton talk – have given me renewed hope.

***

We have a daughter who is a low ability swimmer. Like other families, every Saturday morning we’d bargain over whose turn it was to take her to her lesson. One half-term became two. Then three. Then four. And yet still she was in Beginners One. She was fine about this – she liked the classes and only causally noted that other children were learning to swim and moving up to the next class.

Other parents said, ‘Don’t worry. Everyone learns to swim in the end. She’ll get there.’ And I knew they were right – she would get there eventually and we should just accept it’ll take her longer than other children. But then someone suggested we try another swimming class. So we did. And from the moment she got into that new pool with a new instructor it was like watching some sort of miracle. By the end of the first lesson she was doing something approaching proper swimming and by the fourth lesson she was good enough to practise on her own at the local pool with us.

Did she just ‘need time’? Was it chance that it ‘just clicked’ on that particular day? Would she ever have learnt to swim in Beginners One at the old place? Was she really a ‘low ability’ swimmer?

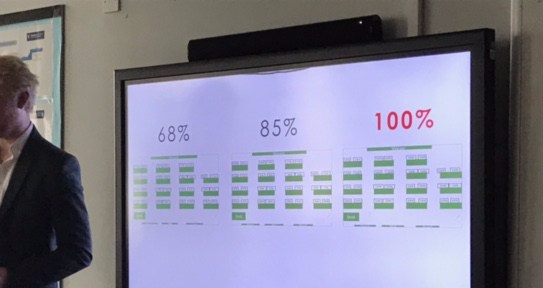

As I was mulling over this small miracle whilst swimming in the local leisure pool on a Saturday (not a tranquil experience that is conducive to deep-thought), I remembered Kris Boulton’s strange picture of classroom desks with a probability that each child learns a concept. This is a photo of him presenting at researchED, but you can also hear about it on Mr Barton’s maths podcast or read his blogpost.

Kris thinks the problem with the accepted educational wisdom is that it deems most instructional methods as fine because some children always ‘get it’. From this observation, they then deduce that other children in the same classroom must be failing for reasons outside the classroom – poverty, genetics, and so on. If you read his blogs, Kris doesn’t deny that these other things are present, but he views these all as factors that increase the sensitivity of the child to instructional method chosen.

Kris has come around to this way of thinking through his study of the work of Zig Engelmann. Engelmann isn’t popular in many educational circles for his commitment to Direct Instruction. But you don’t have to be a fan of D.I. (I’m not particularly) to admire the scientific approach he has taken to constantly refining his programmes of instruction. And at the heart of the approach he takes is the following belief:

The best instructional methods will close the gap between those students who have a high chance of understanding a new concept and those who have a lower chance of understanding it.

This! This way of thinking about inequalities in rates of learning is simply not part of the narrative for many policy-makers and researchers. There are some children who will ‘get it’, regardless of instructional method used (the Autumn-born middle-class girls in infants and the kids in my daughter’s first swimming class who raced through and onto Beginners Two within a term). Then there are those for whom the probability that they learn the new concept is highly sensitive to methods of instruction. My daughter wasn’t a ‘low ability’ swimmer; she was just a novice swimmer who was more sensitive to instructional methods than others for whatever reason.

I don’t know whether Zig Engelmann has ever thought about swimming instruction, and I don’t know what he would make of the methods used to teach my daughter in the second swim school. Who knows whether her swim instructor has given much thought to questions of sequencing and the benefits of what Kris calls atomisation in his blogpost. I’m confident that she is not following a Direct Instruction script! But just imagine if the method of instruction she has devised through years of experience could be codified, at least in part, so that other instructors could follow it too.

There will always be differences in how easily humans are able to learn new concepts, but I’m more convinced than ever that we can reduce the size of these gaps in rates of learning by paying close attention to the instructional methods we use. An instructional method doesn’t work if only some children can succeed by it. Let’s work on developing methods that give every child the highest possible chance of succeeding.

Coda

I showed this post to Kris and he wrote:

Engelmann has applied his ideas to physical activity, including tying shoelaces, doing up buttons, and I think some aspects of sport. I had an excellent instructor for Cuban Salsa a few years back. She created three 10 week courses, at differing levels, and broke everything up into different moves, from small components up to more complex combinations. One evening several of us went out to a dance event that had a lesson with a different instructor – he spent most of the time saying ‘No-one can really teach you how to move, you just have to feel the music.’ Utterly useless.

(I think those last two words are his less polite way of saying that he is a novice dancer who is very sensitive to instructional methods!)

Kris is a little further on in his journey than me, as he explains here. He believes so strongly that this is how we reduce inequalities in rates of learning that he is joining Up Learn, a company dedicated to this same belief, that is putting the theory into practice and believes they can use it to guarantee an A or A* to every A Level student who learns through their programme.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

This is really interesting Becky (and I say this as a mother of a ‘high ability’ swimmer who is as stubborn as I am…)

I just wondered apart from instructional technique what other factors came along with the new swimming teacher. My daughter has been lucky to have always been taught by the same swimming teacher who has more than 25 years of experience and who has 3 daughters who she also taught to swim who went on to represent their countries at junior level). I wonder if the same efficacy graph we see for school teachers also applies to swimming teachers?

This is sorta what Bold Beginnings is trying to say. I think.

Pingback: What Teachers Tapped This Week #17 - 22nd January - Teacher Tapp